Sacred Journeys 9th Global Conference, 5-8 July 2022 in Piran/Portoroz, Slovenia

Scholars will find any excuse to attend an academic conference if the venue will be in a scenic place far from home, especially if they do scholarship on the phenomenon of travel. In this case the “excuse” was to participate in a conference on the subject of pilgrimage and religious tourism—a topic that in recent years gets increasing attention in humanities, social sciences, political science, religious studies, philosophy, and you-name-it other fields of academic research. This event was an opportunity for me to meet and share with these lively and inquisitive, warm-hearted folks whose interest in pilgrimage invariably goes much beyond mere academic observation and analysis. Presentation topics ranged widely, including (for example) an account of a dying pilgrimage complex in southern Japan; a visually dramatic and self-reflective journey on a “vertical pilgrimage” in the form of scaling the rock face of El Capitan in Yosemite Park, California; an insightful stakeholder analysis of a nocturnal pilgrimage in Mallorca; and (by yours truly) a consideration of “Pilgrimage Hagiography as Re-enchantment: The Case of Chaitanya’s Journey to Vrindavan, India.”

Of the several interesting themes that emerged from the two days’ presentations (including a few online), a fairly common one was the scholars’ reflections on their own experience in the process of researching their subjects. One presentation I found particularly interesting was by Rebekah Scott. Several years ago, she and her husband bought a house in a small village—Moratinos—in northern Spain and moved there permanently (from the U.S.A.) to host pilgrims traveling on the Camino de Santiago (Way of St. James). I was happy to receive from her a copy of her memoir A Furnace Full of God (www.peaceablekingdomcamino.com). Having now, some days later, read it to the end, I marvel at her sharp writing ability and her tireless resolve to be there for others as she witnesses and supports pilgrims’ transformations and undergoes her own. She also observes how the spirit of this particular pilgrimage way has changed over the years:

What was a rugged path of repentance and suffering is now a series of day-hikes for spiritual consumers. The bare-bones infrastructure for ascetics has become a cheap holiday attraction for those whose eyes glitter at “something for nothing.” The historic Pilgrim Way is a collision of Capitalism and old-time Christian simplicity. The outcomes are fascinating, moving, and sometimes grotesque. We live in the middle of it.

Much the same might be said about pilgrimage—and tourism—to and in Vrindavan, the sacred home of Shri Krishna during his childhood in very ancient times. But more on this shortly. In her book, Rebekah also shares heart-wrenching tragedy, as her dearest friend in their village, Angela, is killed in a car crash. There was nothing Rebekah could do but take to the Camino herself and dedicate to Angela her pilgrimage and all her devotions in the many shrines and churches along the way to Santiago de Compostelo. Her hope and conviction was that pilgrimage on her friend’s behalf would at least shorten the duration of time her untimely departed friend would have to undergo the trials of Purgatory—the place, according to Roman Catholic tradition, where souls may become fully purged after death in preparation for heavenly beatitude.

Rebekah’s referring to Purgatory in her book prompted my own “comparative” thoughts on the notion of purgation, and this brings me back to the subject of my presentation at the Sacred Journey’s conference:

As I told ever so briefly in my very time-bound presentation, Shri Chaitanya’s early 16th century 1600-km journey by foot to Vrindavan from Puri included, according to his main sacred biographer Krishnadas Kaviraj, passage through the Jharikhanda forest (in the present-day Indian state of Jharkhand). Readers of this account are treated to a description of an amazing—seemingly fantastical—assembly of various forest animals among which natural predators and prey abandon their animosities to “chant” Krishna’s names, dance, embrace and even kiss each other, all at the inspiring behest of Shri Chaitanya. Witnessing all this fun, Kaviraj writes, Shri Chaitanya thinks himself to be already in Vrindavan where, likewise, all animosity among the species is absent. He recalls a stanza from the sacred Sanskrit text Shrimad Bhagavatam (10.13.60):

Vrindavan is the transcendental abode of the Lord. There is no hunger, anger or thirst there. Though naturally inimical, human beings and fierce animals live together there in transcendental friendship.

What does this Jharikandha story have to do with Purgatory or purgation? Superficially, little—and more deeply, a great deal. Arguably, for followers of Shri Chaitanya (and those of all other Indic religious traditions), this temporal world in which we presently dwell is already purgatory—a place for being purged, for allowing ourselves to be purged of our forgetfulness, our alienation from God. Such purging can be a long process—over countless lifetimes, including lifetimes as so many different animals—or it can be a short process occuring in this one rarely achieved human lifetime. Krishnadas Kaviraj would have his readers treated to a vision of the shortest possible process of purification: You come into contact with divinity by hearing God’s names, sung by one who is God-intoxicated such as Shri Chaitanya, and despite yourself—or despite having even a nonhuman body—you become utterly and thoroughly purged of all the grime of self-centered illusion and delusion encrusted on the “mirror of the heart” (as Shri Chaitanya expresses it in one of his eight preserved Sanskrit prayers).

Well, this is somewhat tangential to the aim of my presentation at the Sacred Journeys conference, which was, in part, to highlight a sharp contrast: There is the Vrindavan of Shri Chaitanya’s (and Krishnadas Kaviraj’s) transcendent vision and experience; and then there is the Vrindavan of today, built-up, conjested, and noisy, to which now an estimated 15 million pilgrims—or tourists—flock annually. To be sure, for those with the eyes to see, the Vrindavan of Shri Chaitanya—and of Shri Krishna long before—can still be seen. But the searing glare of a globalized, distorted facsimile of that vision competes fiercely with the earlier salubrious vision. The problem is that Vrindavan’s present-day visitors may very well miss out on what Vrindavan has to offer in the way of speeding up their purgation process. Vaishnavas (those who regard and worship Vishnu or Krishna as the ultimate and supreme Lord) tell us that this purgation process can be radically accelerated by hearing from sadhus—the persons who, especially in Vrindavan, have dedicated their lives to Krishna-seva—constant attending to Krishna’s service and avoiding as much as possible harming other living beings. Alas, the throng of Vrindavan’s would-be pilgrims are likely to pass by such sadhus, thereby missing the higher purpose of their journey.

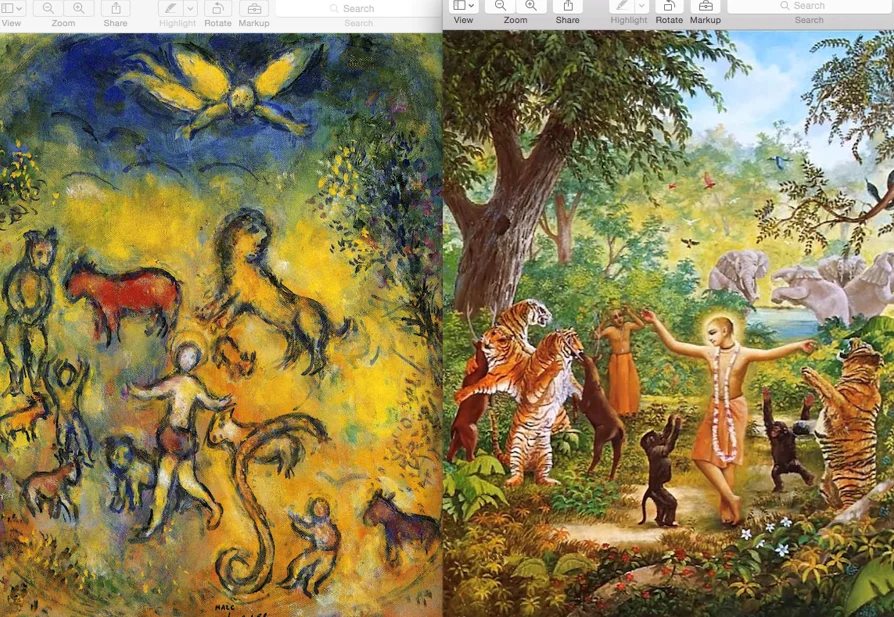

Speaking of comparison, a few days ago my old friend and prolific author Steven Rosen (www.sjrosen.com) posted this image (below), juxtaposing Marc Chagall’s painting “Reconciliation of all the Creatures” (1958?) with an illustration of Shri Chaitanya’s Jharikhanda animal celebration (printed in Bhaktivedanta Book Trust’s edition of Krishnadas Kaviraj’s Caitanya Caritamrita). Pondering on these images as I watch my neighbor’s black and white cat hunting mice in the adjacent cornfield, I wonder at the two graphic art visions of interspecies harmony on the one hand and the reality of biotic violence on the other, and of the possibility—the opportunity—of a purgatory in between. Put another way, I wonder if the sometimes clear, sometimes obscure dividing line between pilgrimage and tourism is marked by whether one is on the short and relatively straight path of purgation (pilgrimage, possibly to be completed in this one lifetime) or on the long, slow and meandering path of purgation (tourism, possibly lifetimes of wandering in ignorance of one’s higher purpose). With these rather meandering thoughts of a would-be scholar of pilgrimage, it’s better I end here, only to confess how greatly I would have liked to witness Shri Chaitanya’s fun with the dancing animals of Jharikandha.